Encounter with an Ancestor: John Perry Barlow

I met John Perry Barlow in 2015 when he moved into the backyard bungalow behind the house where I lived in Palo Alto. My landlord Rob, a die-hard deadhead, had offered the Grateful Dead lyricist a 1992-era rent rate, and John Perry was glad to accept. At the time, he was struggling to develop a startup called Algae Systems that made bio-fuels out of microwaved sewage, plus he had alienated much of his community by getting into a relationship with a woman who was the same age as his daughters, my age.

One of the first times we hung out, it was 10pm when he suddenly remembered, “That poetry thing!” and that was all the information I had to work with when he invited me to an event in San Francisco. His girlfriend stayed behind, and I drove John Perry from Palo Alto to San Francisco in the vintage Mercedes Station Wagon I’d been foolish enough to buy with my starving artist income. As we traveled northward on the 101, it struck me how eager he was to hear my story of growing up in Texas and then struggling at Stanford, and how he asked excellent questions.

With a smile, John Perry ranted about how the word “content” was a horrible term to refer to internet media, since it isn’t “consumed:” it’s reproduced every time it is experienced. Real content, material stuff, gets used up when consumed, and using this term to describe internet media prevents people from understanding the nature of this ever-replicating phenomenon. John Perry had strong opinions about things I’d never thought about, and I felt refreshed by his depth and sincerity.

Sometime after 11PM, he and I ascended the stairs to the rooftop deck of an ex-googler’s San Francisco home, with skyline views and a classy fire pit. Our host, a man in his 40’s, seemed to have achieved an abundance of money from working at google, and after retiring had achieved an abundance of time. He shared that abundance generously with John Perry and me, pulling open the warming drawer to reveal two plates with juicy steaks that he had marinated and grilled, with vegetables.

The dinner came with one rule: in order to eat, one must read a poem they’d written. Everyone else had already read their poem, and eaten. John Perry was exempt for reasons I didn’t yet understand, so it was my turn, and the steak was already right there on my plate, warm. With an audience of five or six people, I got out my phone and read a draft of something I’d been working on, “Four Leaf Clovers Rarely Hide.”

“Huh,” John Perry grunted, relieving me of the spotlight of the group’s attention. “That was a real poem.” We obviously wanted to know what he meant by that, so he elaborated. “I mean, it’s either a poem or it’s not.” At that moment in my journey, I could tell the difference between the words and the energy that the words generate in a listener, in a given time and place. That my words had been “a real poem” to John Perry turned out to be jet fuel for my writing efforts.

Spending time at his house, my world became richer. To John Perry, the crows who woke me in the mornings weren’t crows at all, but “juvenile ravens,” who travel in flocks, like crows, before growing larger and pairing off. John Perry bristled when I spoke disparagingly of “Shallow Alto,” and I soon realized that one needed to scratch the surface to realize the deep weirdness of this place that had seemed so buttoned-up to me, the heart of Silicon Valley. He had a way of elevating everything in his presence, bringing out its magic and mystery. With fascination and curiosity, he welcomed the many people who came into his life. According to a mutual friend, "he would say he didn't know everyone in the world but he was trying."

Though I’d lived for years in Rob’s Palo Alto houses, each one each one of which was named after a Grateful Dead song, I was unfamiliar with the Grateful Dead and learned about its local origins from John Perry, how they’d gotten their start making music to stabilize the momentum of the Acid Tests, massive parties where people took LSD in small cups of kool-aid or punch, then danced for hours in a reality that unfolded around them. The music wasn’t organized in “songs,” but in long meandering improvisations of words and tones and rhythms that held the space in a friendly embrace.

Whenever he told a story, he gave the impression that he had rehearsed it many times, and that each re-telling was another rehearsal for future re-tellings, and yet he also made an effort to customize the story’s telling for that specific moment, inhabiting that space as fully as possible while transporting his listeners into the world of the story.

After only a few months of living in the backyard bungalow, John Perry’s health failed, and an ambulance took him to Stanford Hospital. Visiting him there, I saw the hospital through his eyes: He described it as a kind of dystopia, made more dysfunctional by the fact that it was a teaching hospital, since it brings amateurs into the room and divides the attention of the professionals who know how to do things. Nearly every time I tried to get from the parking structure to his room, I got lost in its labyrinth.

He was glad to be discharged to a rehab facility, a five minute bike ride from our houses. The face of the one-story building was reflective glass, so I could watch my reflection biking toward the building, dismounting, taking off my helmet. It was during one of my visits to him there that he told me the story of how the Grateful Dead got its name. Semi-reclined in his hospital bed, he held court with me and my landlord, Rob, who indicated that he had heard the story before and was eager to hear it again.

According to John Perry, one of the band members had opened a thick dictionary and put their finger down on a random page, landing on the entry for a folktale: a young man leaves home to set out on his life quest, and in the very first town he reaches, he encounters a dead man, too poor to pay for a funeral and no apparent family The young man spends his inheritance to give the penniless stranger a proper burial, and that night, the dead man’s spirit visits the young man’s dreams, dancing and offering his gratitude. They might have landed on another random entry first and skipped it before finding that one, he said, but that was the story.

“Before you go,” he said, “can you scratch my back?” He turned to his side, and his skin was moist with sweat and streaked with pink sheet marks. As I scratched, he stretched and moaned with pleasure as pure as a housecat.

Instead of rehabbing and returning to the bungalow, as hoped, his health took another decline in the rehab facility, and this time he was transferred to a hospital in San Francisco, with epic sweeping views of the Golden Gate and the city. His daughters and ex-wife came from out of town to accompany him and manage his care, nudging Girlfriend out of the picture, all of which John Perry welcomed. I was surprised that Elaine, who had smiled and introduced herself as “the ex,” called him John, and I soon learned that most of his closest community did as well. By then, I’d already committed to the double-name, and when I checked in with him, he didn’t mind, so John Perry it was, for me, or sometimes Barlow.

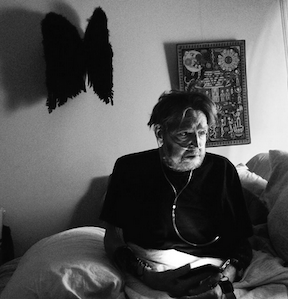

After staying in at least one additional hospital in San Francisco, John Perry eventually settled into an adjustable bed in the home of his dear friend and collaborator John Gilmore, with whom he had co-founded the Electronic Frontier Foundation. I was among the strange cast of characters that surrounded him during that time, while he navigated the challenges of surgeries, infections, specialists, and a body that was failing after a poetic life of cattle ranching and debauchery.

He posted frequently to facebook and twitter, and during the middle of a conversation, he wasn’t shy about turning his attention to his phone in his hand, plugged into the charger next to his hospital bed. His constant mental stimulation also included television, including History Channel documentaries about Ancient Egypt. Several times we saw a commercial featuring a person playing tennis against a giant foot that was infected with reddened skin between its massive toes. It advertised a drug for Athlete’s Foot, and by the end of the commercial, the human defeats the giant foot in tennis, while the giant foot’s infection was also healed, glowing baby skin.

“For everyone to do acid,” he remarked, “Not everyone has to do acid.” In poetic form, he described how if a portion of the population does acid and then shows the rest of the population something that the drug inspires, the rest of the population experiences the acid itself, through the media. Anyone with a television can see the giant foot playing tennis.

He had a device called the A-linker, a yellow adult-sized tricycle with no pedals, which allowed him to walk and balance and stand. He wrote about how much joy he received from going into the park and making eye contact with strangers.

He was writing a book of his life stories, and he wanted my help writing it, so one night in late 2017, I spent a night as his caregiver. I appreciated working alongside his team to see how different people worked. One young Nepalese woman, Tenzin, kept a hand on Barlow anytime he was within reach, rubbing his shoulders and petting his arms. According to her, constant touch was part of the caregiving style in Nepal. John Perry loved it, and it made plenty of sense to me.

There was a nurse who went off duty shortly after the start of my shift, and during our brief overlap, while she oriented me to his oxygen machine, she shared with me how being a nurse was not a big deal. “Everyone is a nurse,” she said, and that offhand comment helped reignite my latent desire to go to nursing school. I wanted to be a part of everyone.

I stayed awake for much of the night as John Perry kept wanting to go to bed, then wanting help getting out of bed, then being too exhausted to sit up or do anything and needing help with getting back into the bed. At one moment he mentioned needing to go over the creek, and I gathered that his restlessness and exhaustion were putting him into an alternate reality.

We didn’t go over the creek, but we also didn’t do any writing.

In the morning, sitting on the side of the bed, he said something to the effect of, “one day we’ll get together and talk through all that we’ve been through here.”

I shook my head, thinking of how much I’d seen him decline in the few years since I’d met him, especially in recent months. “I’m not sure.”

“Hmm,” he nodded, “There were times on the ranch that were like that. After the end of a long night, we’d just look at each other, knowing.”

We looked at each other and nodded, knowing.

“Just getting out of bed requires a tremendous level of heroism,” he told me. It’s hard to estimate how much physical and spiritual pain he endured in those times, especially after I learned that he had been taking frequent doses of LSD, which makes everything more intense.

John Perry Barlow did not want to die. He’d already died once during those illness years, no heartbeat, no breathing, and he was resuscitated back into consciousness. After decades of saying with certainty that there’s nothing but love on the other side, he had visited the other side, and for him it had been nothing but nothing, just gone. It’s fully possible that he had experienced what many people report, clarity and a complete review of the love that one gave and and received during life, but he had no such memory, and he was terrified of dying.

A few weeks after after my night with him, he got a wave of energy and clarity, and during that wave he finished a draft of his book, met his first grandchild, and took a ride across the Golden Gate Bridge in his 1960’s Chevrolet El Camino that had been parked in front of Rob’s house for over two years.

John Perry died not long after that, and according to his wishes, his family hosted a memorial concert at The Fillmore in San Francisco, where for $5, people could see various members of the Grateful Dead Family pay tribute to this man who had influenced their lives. While I waited in line with Rob, outside the building, someone put a food-filled plastic bag on top of a trashcan lid, then walked away, and before I knew it, I was helping to unpack the bag and distribute its contents, which included pouring orange juice into tiny cups, like those paper cup ketchup receptacles at old fast food stores.

The memorial concert was filled with a mix of people who knew John Perry directly and people who had devoted themselves to following the Grateful Dead, with musical acts interspersed with eulogies. Halfway through the event, they showed a short documentary about his cattle rancher era. John Perry’s own voice resounded in that room filled with tie-dye and altered states of consciousness, and he told the story of when he stopped at his family’s ranch on a cross-country motorcycle ride, and, due to the ranch needing help, he stayed there for seventeen years.

Over 70’s color film footage of a young John Perry Barlow laying out feed for cattle, his gravelly elder voice described how a ranch is a civilization with more cows than humans. He brought so much warmth and wonder into people’s lives, even in death, transporting us from a massive San Francisco party to a distant ranch from decades prior, then back again. I don’t remember seeing anyone crying, which somehow felt sad to me. I guess it was hard to express how deeply he was missed, and that space wasn’t quite right for opening the door to that sadness. We'd find other ways to mourn his crossing of the threshold.

On our way out of the event, John Perry’s daughters handed out posters that featured a skeletal cartoon of JPB on a motorcycle, with the words, “Congratulations on your graduation from meat-space.”